The Freedmen's Bureau: Advancing Education and Financial Literacy in a Post-Civil War America

by Alex Nellis

In a recent blog post, we explored Freedom's Journal and the impact it had on the Civil War. There are a number of moments in Black history surrounding the Civil War that aren't often explored in school textbooks. Another little-discussed (but important) part of the Civil War history is the Freedmen's Bureau. The Bureau was established in hopes of helping newly freed African Americans gain financial independence.

The idea of the Bureau was first conceived as a result of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. A Massachusetts congressman named Thomas D. Elliot believed the federal government needed to help newly freed African Americans become financially self-sufficient. When he first introduced the bill, it was unsuccessful. Other congressmen did not see any need for the government to spend money on such a program.

However, Elliot was determined that the program was necessary. Because they were enslaved, it was very uncommon for African Americans to be educated on financial matters at the time. Elliot believed that because the government condoned enslavement, it was the government's responsibility to teach African Americans what society had not previously allowed them to know.

In December 1863, Elliot reintroduced the bill, despite it being struck down the first time. The bill was the subject of significant debate. Many senators believed that everybody needed to advocate for themselves, and that it wasn't the government's responsibility to right previous wrongs.

Slowly, many senators began to see the value in the Bureau's creation. Through much debate, they understood that it was not reasonable to expect African Americans to be financially self-sufficient, when the government had previously disallowed them from being educated in it. Despite the strong arguments, there was still some fierce disagreement. About half of Congress believed the bill should be passed, while half still did not.

18 months after its creation, the bill was barely passed. The House of Representatives voted in favor of creating the Bureau, under the argument of government responsibility to aid with political and social reconstruction, with a 69-67 vote ratio. Had even one person voted a different way, the vote would not have passed with a majority.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law in 1865. However, to get the bill passed, some sacrifices had to be made. The bill was only conditionally approved for one year, and the Bureau's mission was kept vague. Because women were not viewed as equals during this time, the bill was written only to encompass men. The Bureau's purpose was to create a system of compensated labor, to aid with supervising abandoned land, and create and operate educational programs for financial literacy. Despite the vague wording necessary to get it passed, the heart of the Bureau's main goal was still to aid newly freed African Americans in their transition to citizenship.

Despite the bill passing, it was an uphill battle to keep the Bureau running. After a year had elapsed, members of Congress who were critical of the bill attempted to get the Bureau shut down. Critics in Congress strategized to frame the Bureau as interfering with African Americans' ability to be equals in society, because their white counterparts didn't get the same financial education from the government. Other critics argued that the Bureau made no real difference and was a waste of government funds.

However, the Bureau still had strong advocates. A senator from Illinois, Lyman Trumbull, fought to have the Bureau approved beyond the original year. Trumbull's efforts were successful despite resistance. The bill passed for another two years, but was vetoed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. However, President Johnson's veto was ultimately overturned, allowing the Bureau to persist.

To shut down voices of dissent, Trumbull argued the mission of the Bureau needed to be strengthened. The Bureau's mission was written to empower African Americans to become self-supporting citizens through helping them become financially literate.

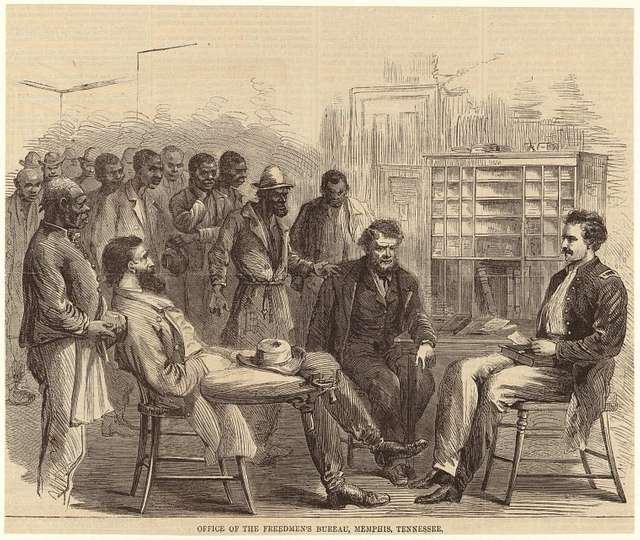

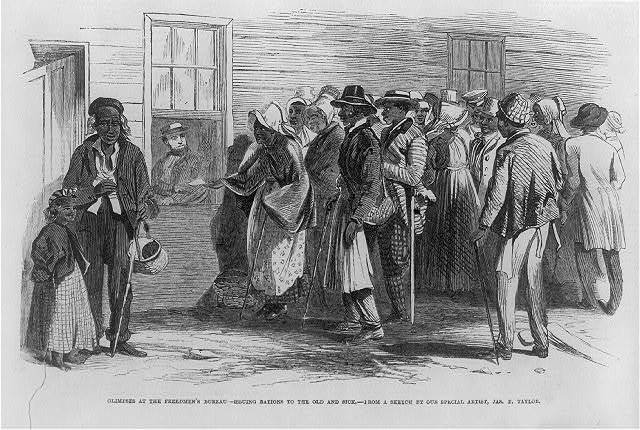

With this support, The Freedmen's Bureau was finally able to flourish. The Freedmen's Bureau became what Dr. W.E.B. DuBois referred to as a "full-fledged government of men." At its peak, the Bureau had offices in 15 states. It was able to provide shelter, medical care, legal services, rations, clothing, and land to thousands of African American families. The Bureau also created labor contracts to provide economic opportunities for African Americans. Through its legal authority granted by the U.S. government, the Bureau also helped protect African Americans from racial harassment and violence. The Bureau's reach eventually extended to include white refugees as well, and also provided the same aid to economically disadvantaged white families.

The Bureau also supported African American schools, and created opportunities for post-secondary education for African Americans. At its peak, the Bureau was even able to create a state-funded public education system. The Bureau surpassed its original intent of providing financial education. With government support, it was able to create educational opportunities for African Americans of all ages.

At its peak in 1869, critics of The Freedmen's Bureau began getting louder. They felt the Bureau had extended far beyond its original purpose. Members of Congress argued that the advocacy to expand the Bureau had led to those in charge taking advantage of government finances.

The resistance against the Bureau was successful. Congress voted to cut almost all funding in 1869. Only the educational programs were able to persist. Throughout the next few years, resistance to the Bureau strengthened, which caused funding to be cut to a point where the Bureau could no longer function. The Bureau was shut down in 1872. Newly freed African Americans once again had little economic protection or education.

Despite how short-lived it was, the legacy of the Bureau lives on. The National Museum of African American History and Culture uncovered the record-keeping system of the Bureau, and has digitized it. You can view the records on the NMAAHC's website. This list provides insight into newly freed African Americans' political and social situations at the time.

The Freedmen's Bureau demonstrates the importance of learning about little-discussed moments in Black history. Educational textbooks frequently frame post Civil War Reconstruction efforts as being largely successful, or don't explore the specific steps the government took to politically reconstruct society. The Freedmen's Bureau shows us the fierce opposition that Reconstruction efforts faced, some of which was successful. The inability of Reconstruction to fully address social and political inequalities also provides us with insight into the continued struggles that communities of color are facing to this day.